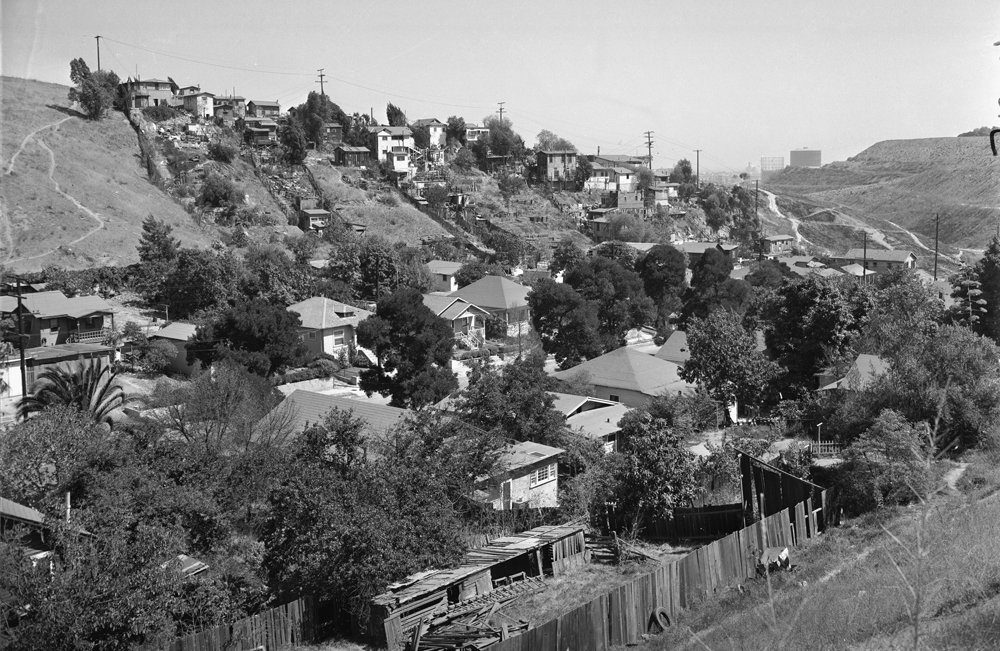

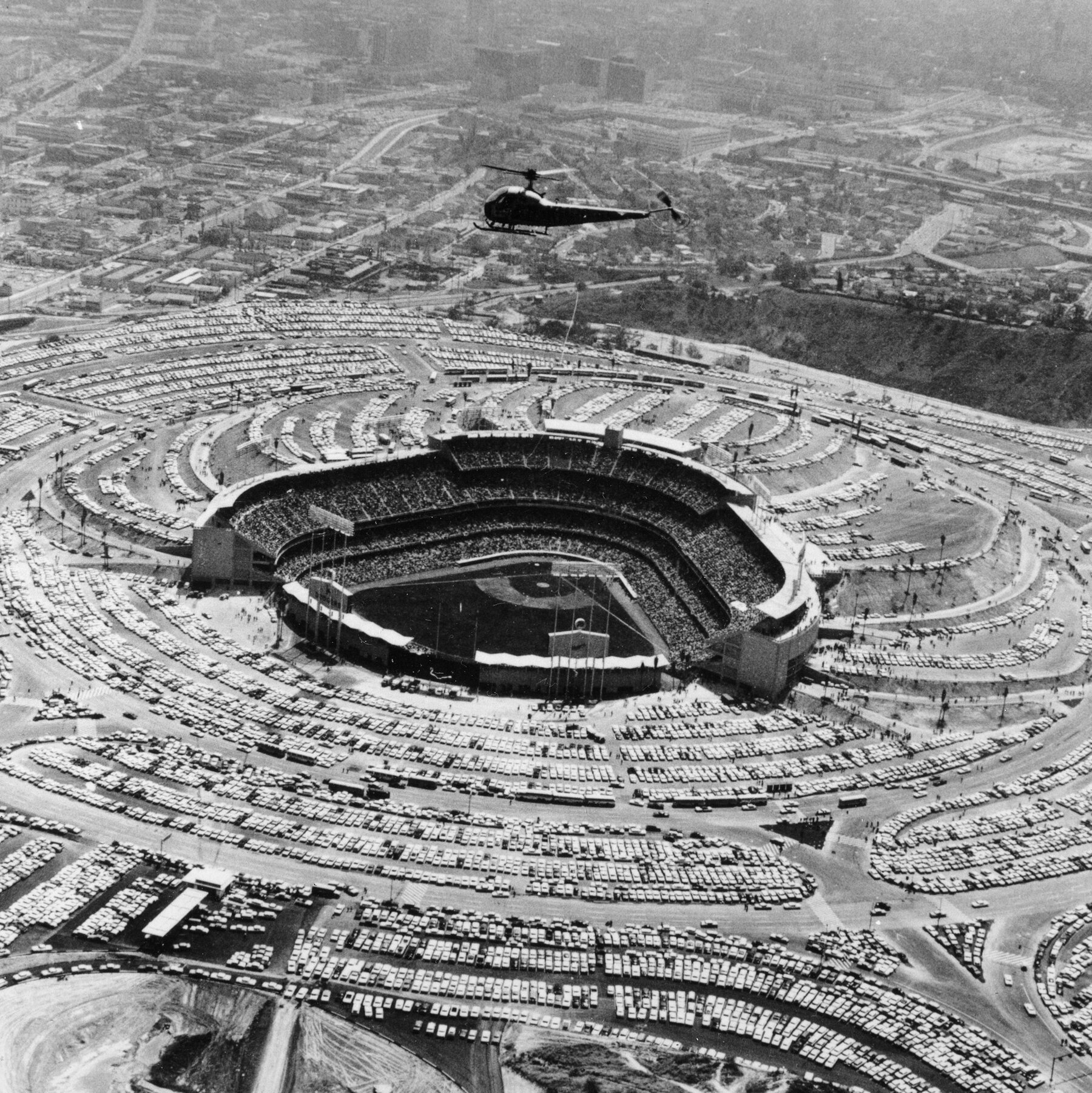

Before the crowd’s roar thundered through Dodger Stadium, blue and white became indelibly imprinted deep in Los Angeles. There was Chavez Ravine, a close, largely Mexican American neighborhood downtown. Chavez Ravine flourished in the 1950s as the vibrant neighborhood was destroyed in the name of progress, its people forced out to make way for what would eventually be the Dodgers’ stadium. Dodger Stadium is now a symbol of baseball excellence, but its rich and complicated history of land, loss, and legacy is behind it. One that continues to haunt the elbow of every home run and seventh-inning stretch.

In the mid-20th century, Chávez Ravine contained a lot of Mexican-American communities that were forcibly removed by a series of governmental actions. The city had initially planned to fill the land with public housing, but as political winds shifted and the political will to build public housing projects also eroded, the land ended up being sold to the Brooklyn Dodgers to build a new stadium when the team moved to L.A. in the late 1950s. Chávez Ravine’s threatened evictions and broken promises remain a painful reminder of the conflicts between the marginalized individuals and pose existential questions about city planning, displacement, and erasure of cultures in American cities. Chavez Ravine was named for Julian Chavez, the first recorded owner of the ravine. He was born in New Mexico and moved to Los Angeles in the early 1830s. He quickly became a local leader.

It was so friendly that many residents left their doors open throughout the day. Chavez Ravine residents were self-sufficient, but the city saw the land as the ideal location for redevelopment since most of the residents were living off the grid without electricity or indoor plumbing. Most families were left under eminent domain by 1951. Between 1951 and 1959, Chavez Ravine was mostly open space. In 1959, the families that remained were evicted from land they no longer owned.

About 1,800 families lost their homes. After many Mexican-Americans got kicked out of their homes, they protested the stadium and the Dodgers. The stadium was still built, but the attendance of Mexican-Americans was low. The Mexican community hated the Dodgers until a rookie named Fernando Valenzuela came along. He Navojoa City in Mexico

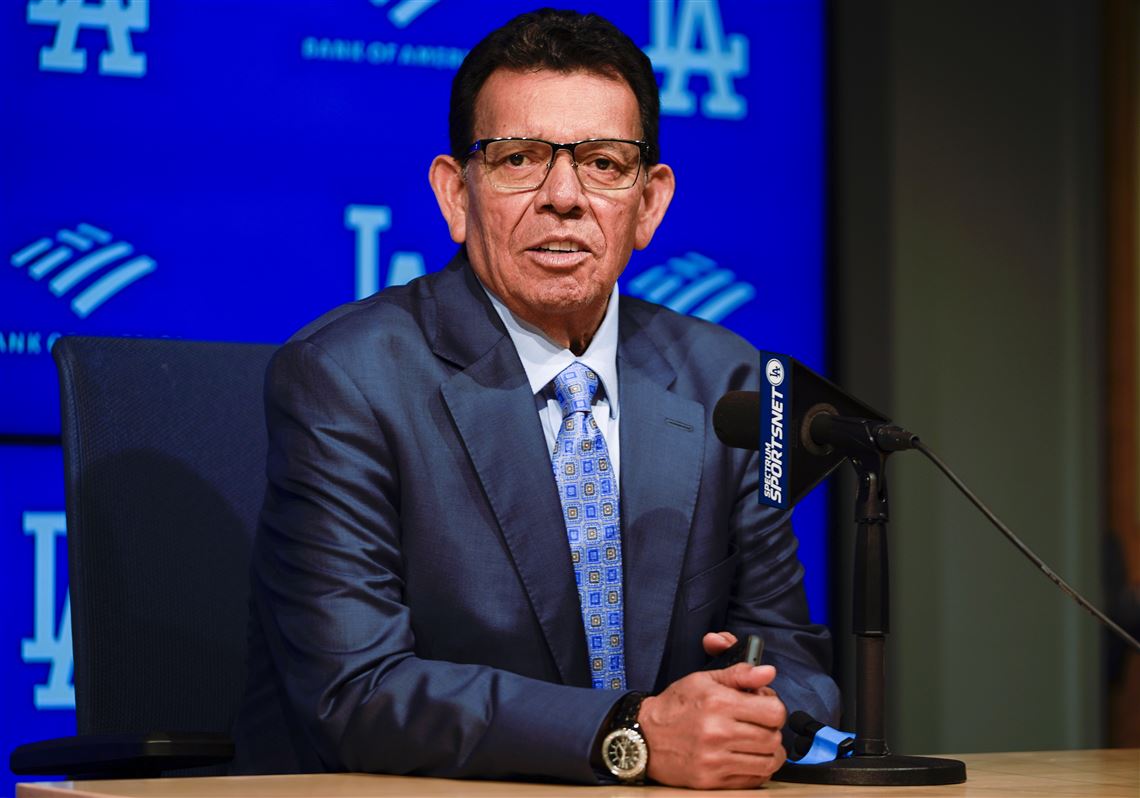

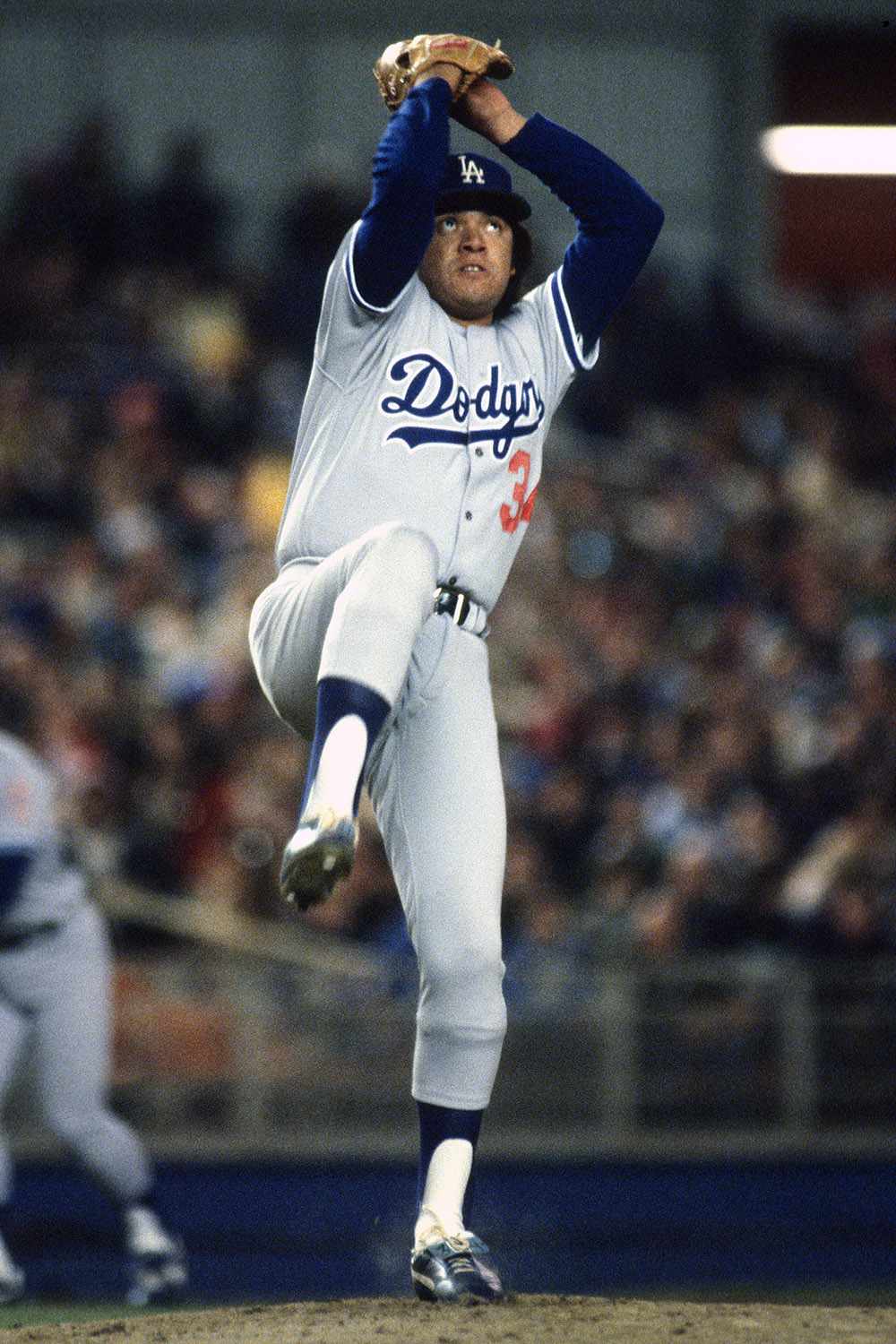

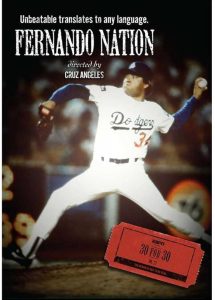

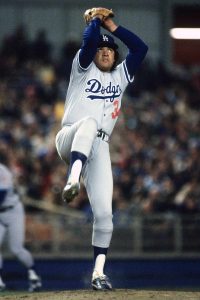

Fernando Valenzuela surprised the Los Angeles Dodgers on the field as well as off the field. During the early 1980s, a cultural phenomenon and an irreplaceable member of the team. Valenzuela burst into superstardom in 1981 with his signature screwball and dark temperament, leading the Dodgers to the 1981 World Series championship as well as to the Cy Young and Rookie of the Year awards, a first and record-breaker. Not only was he a dominant hurler, but he also drew huge crowds, especially of the Latino fan base, who created a wave of popularity and gate attendance for the team that became famous as “Fernandomania.” Off the field, he mobilized a multiracial group of fans and gave the Dodgers franchise new life and dignity when it most needed it.

Later on, he became a Spanish sports commentator for the Dodgers. Sadly, he passed away in 2024 at the age of 63. The Dodgers honored him by wearing a patch with his number on it during the 2024 World Series. Even this season, they are still paying respect to Fernando by wearing the patch on their uniforms. They also retired his jersey number 34.

Ultimately, the Dodgers and Chavez Ravine stand as a painful reminder of where sports, politics, and neighborhood intersect. Despite how much Dodger Stadium is loved today as a cultural institution and symbol of Los Angeles pride, its genesis is based upon a history of removal and dislocation. The history of Chavez Ravine reminds us that progress is always paid in full, and that the poor will never be silenced. Even as today’s Dodgers thrive and inspire generations of baseball enthusiasts, the Chavez Ravine story is not just a background to baseball history, but a testament to the strength of resilience and the value of remembering the entire story.